The phrase "trademark distinctiveness" generally refers to the location in which a particular mark falls on the "continuum" or "spectrum" of distinctiveness outlined in U.S. trademark law.

Put simply, marks that are generic or descriptive in nature inherently lack trademark distinctiveness, and are thus not protected under trademark law.

However, marks that are suggestive, arbitrary, or fanciful in nature are seen as having inherent distinctiveness, and are thus offered intellectual property protections.

In this article we'll explore the basics of the trademark distinctiveness spectrum and how distinctiveness relates to the relative strength of a particular mark.

Note, however, that it's often wise to review your mark with an attorney before you attempt to register it with the USPTO.

While the legal information outlined below is helpful for marks that are arbitrary or fanciful in nature, it's smart to talk over your options if you want to register a mark that falls in the grey area between suggestive and merely descriptive.

A Quick Overview of the Trademark Distinctiveness Spectrum

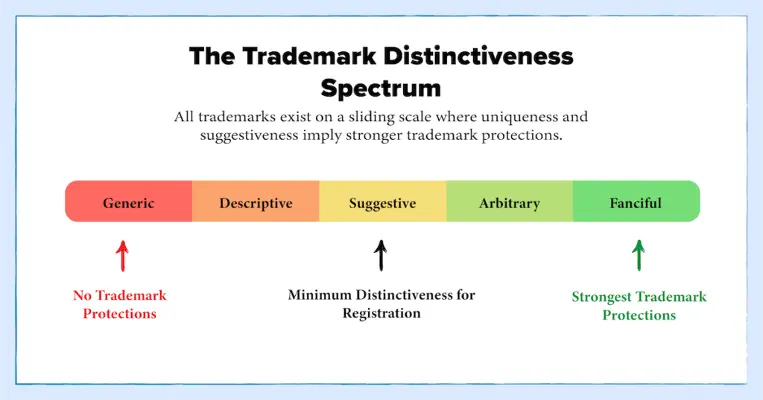

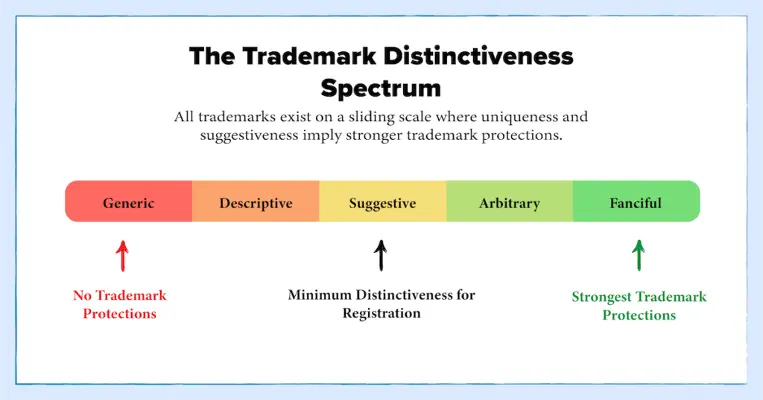

This chart depicts the spectrum of trademark distinctiveness. The further to the right your mark is, like more likely it is that your mark is distinct from your competitors.

All trademark exist on a spectrum of distinctiveness that directly correlates to the strength of the intellectual property protections provided to the mark.

This spectrum of distinctiveness can be broken up into several different sections that each provide progressively stronger distinctiveness and trademark protections:

- Generic — Marks that use the common name for a particular product or service.

- Descriptive — Marks that describe a particular attribute of a product or service.

- Suggestive — Marks that suggest or hint at a particular attribute of a product or service.

- Arbitrary — Marks that have no correlation with the product or service they're attached to.

- Fanciful — Marks that are completely made up and have no formal meaning in the language outside their use as a trademark.

We'll outline each of these distinctiveness categories in more detail below.

However, please keep in mind that all marks exist on a subjective spectrum of distinctiveness, and there are no real hard guidelines on where to draw the line between each of the categories.

Critically, this is why it's always wise to choose a mark that is as far from descriptive as possible, as descriptive marks are offered no protections under trademark law.

Generic

The term "generic trademark" generally refers to brands that use the common name for a particular product or service instead of trying to distinguish themselves from their competitors.

For example, a store could sell a bag with the words "Tortilla Chips" as a generic option. However, it would be impossible to gain trademark protections for such a brand.

Of note, this is one reason why "generic" forms of medicine (such as acetaminophen for Tylenol) are relatively common and cheaper than their competitors with registered trademarks, as they can be produced and sold at wholesale prices without any kind of marketing budget or administrative overhead.

From a legal standpoint, it is never advantageous to market your business under a generic name because (1) it provides no intellectual property protections whatsoever, and (2) it provides no competitive advantage that can help your business stick out from your competitors.

Trademark Grade: You should never use a generic product or service name to market your brand.

Descriptive

Descriptive marks generally include words or phrases that describe a central attribute of a particular brand, product, or service in a way that draws a direct comparison or qualification for that attribute.

In most cases, descriptive marks cannot gain trademark protections except in cases where the brand spends a considerable amount of time, effort, and resources to make the word or phrase have a "secondary meaning" in relation to the core brand.

For example, American Airlines (an airline that provides services in the Americas) and International Business Machines (IBM) (an IT and consulting business) are both descriptive marks that have gained trademark protections over time after acquiring such a secondary meaning.

After all, there are several airline companies in the Americas, but there is only one "American Airlines."

Put simply, if an otherwise descriptive mark is used and advertised exclusively as if it were a trademark for an extended period of time, that mark may gain a secondary meaning relating to the brand and can thus be registered as a principal trademark.

However, you should note that this is an inherently risky strategy due to the relative difficulty and cost of gaining secondary meaning for a descriptive mark.

Generally speaking, such a strategy is only advantageous for large businesses (such as Mcdonalds or Johnson & Johnson) that have the marketing resources available to gain national recognition for their mark.

Trademark Grade: You should try to avoid descriptive trademarks at all costs. This is because descriptive marks (including surname marks or marks with words like "best" or "quality") lack any kind of distinctiveness are are generally not offered any protections under trademark law without first gaining a secondary meaning as described above.

Suggestive

A suggestive mark is composed of words or phrases that merely suggest or hint a particular quality or element of the brand, product, or service without going so far as to describe the product.

For example, the "Netflix" brand is built around a combination of the words "net," referring to the internet, and "flicks," a synonym for movies.

Other notable suggestive marks include "Microsoft" (a combination of "microcomputer" and "software"), KitchenAid (referring to products that provide "aid" in the kitchen), and Greyhound busses (referring to the racing dog).

Put simply, suggestive marks walk the line between descriptive and arbitrary marks by merely hinting at a quality or attribute that relates to the core brand (such as "speed," "efficiency," or a material component such as "microcomputer").

Trademark Grade: Suggestive marks provide a good balance between meaningful trademark protections and the inherent sales appeal and ease at which you can market such a brand to the public.

Put another way, small businesses can often gain sufficient trademark protections through suggestive marks without having to spend as many marketing resources on educating the public about the brand, product, or service.

While arbitrary and fanciful marks are often more advantageous for businesses with larger budgets, suggestive marks provide a good middle ground to small and growing businesses that may rely on local listings and search queries such as "plumber near me" for new customers.

Arbitrary

An arbitrary mark is composed of words or phrases that have a common meaning in a certain language but no suggestive or descriptive relation to the brand, product, or service in question.

For example, in the English language the word "banana" has nothing to do with computers or any other form of technology.

For this reason, if a business were to name itself "Banana" and sell computers, this trademark would be "arbitrary" in nature due to this core disconnect between the word and the brand.

As a few quick examples, some common arbitrary trademarks include Apple computers, Dove chocolates, Camel cigarettes, and Shell gas stations.

Trademark Grade: Arbitrary marks are considered to be inherently distinct (as they do not suggest or describe anything about the product or service they relate to) and thus possess strong trademark protections.

However, since many arbitrary marks include relatively common words (such as "apple" or "camel"), it's critical that you perform a thorough trademark search to ensure no one else has used or is currently using the word or phrase in a similar industry.

Fanciful or Coined

A fanciful or coined mark only has a meaning when applied to a particular business's brand and products.

Put another way, these are words or phrases that are "made up" purely as a marketing tool, and have no definition or meaning outside of the contexts of the brand, product, or service.

A few famous examples of fanciful marks include "Xerox" for photocopiers or "Nikon" for precision electrical equipment.

To expand on this a little, fanciful marks are often misspellings, abbreviations, or puns that are used to market the brand in a fun or interesting way.

The Nikon brand name, for example, is a westernised abbreviation of the company's original full name that it used to market camera equipment in the 1930s and 40s.

Specifically, "Japan Optical Industries Corporation" (日本光学工業株式会社) became "Nikkō" (日光) which was then westernized to "Nikkon."

Trademark Grade: Fanciful or coined trademarks are at the highest end of the distinctiveness spectrum and receive the most protection under trademark law.

However, it can also take a significant amount of time, money, and energy to market a fanciful or coined mark to the public, as they present a higher barrier to brand recognition.

Why is Trademark Distinctiveness Important?

Trademark distinctiveness is the most important element in determining the strength of your intellectual property rights.

Put simply, trademark distinctiveness is important because it is the first step in the legal process of gaining intellectual property protections for your brand, product, or service.

Specifically, the act of gaining trademark protections for your brand will generally follow a certain logical path:

- Determine whether the mark is distinct enough to cause consumer confusion if a different brand would begin to use it. If so:

- Perform a cost/benefit analysis to determine if the business would benefit from registering the mark as a trademark. If so:

- Attempt to register the mark on the Principal Register so you can gain trademark protections for your brand. If you are successful:

- File a combined Section 8 Affidavit of Use and Section 15 Affidavit of Incontestability after five years of continuous use to prove the mark is still being used in commerce and to gain incontestability protections for your mark (a significantly stronger form of IP protection). After that:

- File another Section 8 Affidavit of Use as well as a Section 9 Renewal of Registration form after ten years of continuous use to renew your mark. Then, take steps to renew your use every ten years thereafter.

Notice how the entire process rests on the idea of reducing consumer confusion by offering protections to marks that are distinct from their competitors.

This idea of protecting the consumer is central to the entire legal framework surrounding trademarks, as making sure that consumers can be confident that the products and services they are purchasing are authentic is the whole point of trademark law.

In the same fashion, ensuring that your brand is distinct from your competitors is a great way to foster consumer confidence in your brand and an excellent way to build a loyal audience over time.

However, all of this starts with ensuring that your trademark is distinct enough to fall under the suggestive, arbitrary, or fanciful categories, as these are the only ones that are offered protections under current U.S. trademark law.

Polaroid Factors and How to Determine the Strength of Your Trademark

Courts will consider several variables (such as the ones outlined in the Polaroid and DuPont factors below) in trademark infringement cases. Working backwards from these factors can help you choose a strong mark.

As we've stated numerous times throughout this article, trademark distinctiveness is the most important thing to keep in mind when determining the strength of your mark.

However, it can sometimes be difficult to determine how distinct a mark is in the grand scheme of things.

This is where case law comes in.

Specifically, in 1961 the U.S. Court of Appeals Second Circuit ruled on Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961).

In this case, the Polaroid Corporation (the owner of the "Polaroid" trademark and 22 other similar registrations) brought an action against Polarad Electronics Corporation, stating that the Polarad brand was too similar to their own (i.e. "not distinct") and resulted in consumer confusion.

The crux of the case was the question of whether the Polarad's electronics products (microwave ovens and television sets) strayed too close to Polaroid's camera equipment.

However, the case also brought up a larger point of "how do we qualify distinctiveness" in cases where two brands operate in similar, though distinct, spaces.

The answer, in this case at least, is to look at the sum of a number of factors to determine if the strength of the prior mark.

Specifically:

Where the products are different, the prior owner's chance of success is a function of many variables: the strength of his mark, the degree of similarity between the two marks, the proximity of the products, the likelihood that the prior owner will bridge the gap, actual confusion, and the reciprocal of defendant's good faith in adopting its own mark, the quality of defendant's product, and the sophistication of the buyers. Even this extensive catalogue does not exhaust the possibilities — the court may have to take still other variables into account.

Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961)

This quotation lays out eight specific factors (plus the "other variable" note) that courts now refer to as the "Polaroid factors of trademark distinctiveness."

Dupont Factors: Another Way to Test Your Mark's Strength

These factors were then reaffirmed a decade later in Application of E.I. DuPont DeNemours & Co., 476 F.2d 1357, 1361 (C.C.P.A.1973), where the factors were changed slightly into a list of 13 specific factors that courts must consider when determining the likelihood of confusion.

Specifically, when testing for likelihood of confusion the court must consider each of the following factors:

- The similarity or dissimilarity of the marks in their entireties as to appearance, sound, connotation and commercial impression.

- The similarity or dissimilarity and nature of the goods or services as described in an application or registration or in connection with which a prior mark is in use.

- The similarity or dissimilarity of established, likely-to-continue trade channels.

- The conditions under which and buyers to whom sales are made, i. e. "impulse" vs. careful, sophisticated purchasing.

- The fame of the prior mark (sales, advertising, length of use).

- The number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods.

- The nature and extent of any actual confusion.

- The length of time during and conditions under which there has been concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion.

- The variety of goods on which a mark is or is not used (house mark, "family" mark, product mark).

- The market interface between applicant and the owner of a prior mark: (a) a mere "consent" to register or use; (b) agreement provisions designed to preclude confusion, i. e. limitations on continued use of the marks by each party; (c) assignment of mark, application, registration and good will of the related business; (d) laches and estoppel attributable to owner of prior mark and indicative of lack of confusion.

- The extent to which applicant has a right to exclude others from use of its mark on its goods.

- The extent of potential confusion, i. e., whether de minimis or substantial.

- Any other established fact probative of the effect of use.

Putting it All Together: How to Determine Your Mark's Strength Through Distinctiveness

When determining the relative strength and distinctiveness of your trademark, it's smart to approach the mark from the perspective of these two lists of factors.

For example, drawing from the final two factors on the Polaroid list, what is the relative quality of your product when compared to other products in your industry? What kind of audience are you trying to target with your products, and how likely are they to confuse your product with a different one?

If your product is of a relatively equal quality to the rest of the market and your target audience is more likely to confuse your product with a similar brand (such as if you sell directly to consumers as opposed to more sophisticated buyers in a B2B market), you may need to establish a more distinct (i.e. arbitrary or fanciful) mark simply because a merely suggestive mark may not be enough to set your brand apart.

Put another way, the strength of a trademark can change depending on the context it is used in and the relative distinctiveness of the mark.

The wider your marketing net, the more distinct your trademark will have to be to stand out from the competition.

Or, put another way:

- Generic trademarks are inherently weak because there are no contexts where they are distinct enough to provide protections.

- Descriptive trademarks are inherently weak because marks that are merely descriptive are not offered trademark protections unless they acquire secondary meaning, which generally requires a great deal of time and money to pull off.

- Suggestive trademarks are of a relatively neutral strength, because they can be distinct in most contexts, but may face pressure from competing brands on the national stage.

- Arbitrary trademarks are generally strong as long as no other brand has used the mark in commerce to market a similar product or service. This is because the lack of a relation between the mark and the product or service in question makes the mark inherently distinct in all contexts without a prior use.

- Fanciful or coined marks offer the strongest trademark protections because they are often made-up words with no use or definition outside of marketing your brand, making them inherently distinct and worthy of the strongest protection.

The key takeaway, then, is that your mark's strength is inherently tied to the mark's distinctiveness, which is itself determined through contextual factors such as the sophistication of the audience, the quality or attributes of the product, and the channels and markets you plan on using your mark in.

Arbitrary and fanciful marks are thus preferred because they possess inherent distinctiveness, provided no one else has used the mark in the past.

Meanwhile, suggestive marks generally have to work hard to prove that they are not "merely descriptive" in nature, which would result in the loss of their trademark protections.

Striking the right balance between the legal distinctiveness and marketability of your trademark is key to determining the relative strength of your brand, product, or service.

Trademark Distinctiveness FAQs

Most questions you might have about trademark registration and distinctiveness can be answered with a quick search on the USPTO website, or by speaking with an experienced attorney.

Individuals who want to register a trademark for their brand will often have questions about the process.

For this reason, the USPTO publishes a list of more than 300 FAQs they believe will help individuals who are registering for the first time.

We'll answer a few of the questions we commonly receive below, but please keep in mind that the USPTO publishes regular resources on their website in case you need more specific information about the trademark registration process.

What is trademark distinctiveness?

The term "trademark distinctiveness" refers to a consumer's ability to identify and distinguish a brand, product, or service from its competitors.

Generic and descriptive marks are generally seen as having no distinctiveness, and are thus given no protections under trademark law.

Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks are seen to have inherent distinctiveness, and thus gain protections under trademark law.

Importantly, distinctiveness is a key element in both the trademark registration process and trademark infringement litigation, as trademark law is based on the idea of reducing consumer confusion by ensuring the products and services of different brands are sufficiently distinct from one another.

Often, this plays out in one of two ways: (1) by ensuring that a mark is suggestive as opposed to descriptive or generic (and thus worthy of trademark protections), and (2) whether two competing marks are confusingly similar.

Why does my trademark have to be distinct?

The USPTO will only allow you to register marks that are distinct in nature, meaning that marks that are generic or descriptive cannot gain protections under U.S. trademark law.

For this reason, any other individual or business can use your mark without repercussions as a direct result of its lack of distinctiveness.

What are trademark classes and how do they relate to distinctiveness?

Generally speaking, your trademark only needs to be distinct within the specific industry you work in.

This is why, for example, Delta Faucets and Delta Airlines can exist at the same time, as one provides bathroom products while the other is an airline service.

The USPTO recognizes 45 individual trademark classes that correspond to all products and services that can be sold in the country.

When you register a new trademark, you'll have to choose one or more of these classes to register under.

Importantly, your trademark protections will only extend to products and services that fall into the classification you file under, meaning that your trademark only needs to be distinct within your target trademark class(es).

How can I tell if my trademark is suggestive or merely descriptive?

You can't. No matter what anyone says, the final determination of whether a trademark is suggestive or descriptive ultimately comes down to the discretion of the USPTO attorney who reviews your application.

Because the process is entirely subjective, it's critical that you always stray on the side of caution and choose a trademark that falls more towards the "arbitrary" side of the suggestive spectrum as opposed to the descriptive side of things.

What's the difference between the principal and supplemental register for trademarks?

Trademarks that are determined to have inherent distinctiveness end up on the USPTO's principal register, and thus gain all of the legal protections offered under U.S. trademark law.

Marks that are determined to be descriptive but have the potential to gain a secondary meaning may instead end up on the supplemental register.

The key difference is that marks on the supplemental register are limited to only the following protections:

- The trademark's owner gains the ability to file trademark infringement lawsuits in federal courts to fight off competing brands.

- The USPTO will not allow other individuals or businesses to register confusingly similar trademarks.

- The trademark will show up in trademark search reports as if it were on the principal register.

- The trademark's owner can use the registered trademark symbol (®) to denote the trademark's status.

Or, put another way, marks on the supplemental register do not have access to the following protections:

- Marks on the supplemental register cannot file for incontestability after five years of use.

- Marks on the supplemental register do not have a statutory presumption of validity, ownership, or distinctiveness (i.e. they have to prove all three in infringement lawsuits in order to be successful).

- Marks on the supplemental register do not have a statutory presumption of the exclusive right to use the mark in commerce.

- U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CPB) will not prevent the import of goods that infringe on the trademark.

- Federal agencies will not press criminal charges against individuals or businesses who counterfeit the goods (i.e. you are limited to a civil suit).

- You cannot use your registration on the supplemental register as a basis for a foreign trademark registration application.

Key Takeaways

To summarize, you should make sure your trademark is suggestive, arbitrary, or fanciful in nature, and that no other business or brand has used it in your industry, before you register it with the USPTO.

Trademark distinctiveness exists on a spectrum ranging from generic (having no distinctiveness) to fanciful or coined (having no meaning outside of its use as a trademark).

All potential trademarks fall somewhere along this spectrum, as determined at the discretion of the USPTO attorney who reviews your application.

For this reason, it's critical that you choose a mark that falls as far away from the generic/descriptive side of the spectrum as possible.

If you have any questions about the distinctiveness of your mark, it's critical that you speak to an attorney immediately to determine if it's worth registering the mark as a trademark.

As we've shown in this article, the relative distinctiveness of your mark will directly impact the strength of the trademark protections provided to it and your chance of success in a potential future infringement lawsuit.

For this reason, distinctiveness is key towards building a strong brand that can carry your business forward into a successful and profitable future.

Key Resources

Further Reading

- Key Differences Between the Supplemental and Principal Register for Trademarks

- United States Trademark Law: The Ultimate Guide

- What is “Likelihood of Confusion” in Trademark Law?

Other Resources

- Trademark FAQs | USPTO — A publication by the USPTO that provides the answers to more than 300 common questions people have about the trademark registration process.

- Common Problems in Applications | USPTO — A publication by the USPTO that covers a few common problems that new filers face when attempting to register a trademark.