La frase "distintividad de marca" generalmente se refiere al lugar donde una marca particular se encuentra en el "continuo" o "espectro" de distintividad, según lo estipulado en la ley de marcas de EE. UU.

En términos simples, las marcas que son genéricas o descriptivas por naturaleza carecen inherentemente de distintividad de marca y, por lo tanto, no están protegidas bajo la ley de marcas.

Sin embargo, las marcas que son sugestivas, arbitrarias o inventadas se consideran inherentemente distintivas, y por ende, cuentan con protecciones de propiedad intelectual.

En este artículo, exploraremos los fundamentos del espectro de distintividad de marca y cómo la distintividad se relaciona con la uerza relativa de una marca en particular.

Es recomendable revisar tu marca con un abogado antes de intentar registrarla en la USPTO.

Si bien la información legal descrita a continuación es útil para marcas de naturaleza arbitraria o inventada, es prudente analizar tus opciones si deseas registrar una marca que se sitúa en el área gris entre lo sugestivo y lo meramente descriptivo.

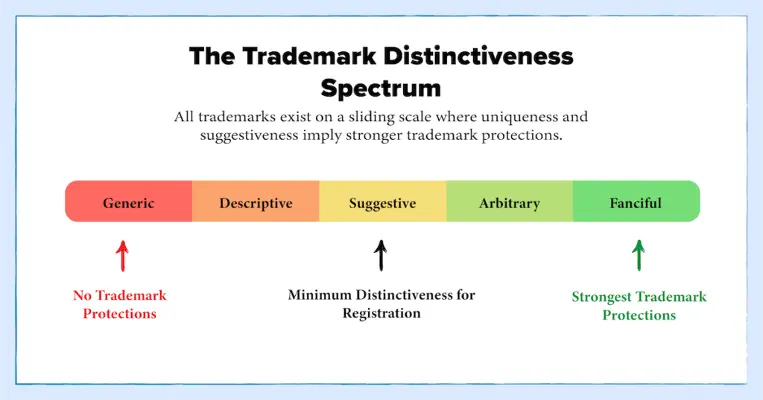

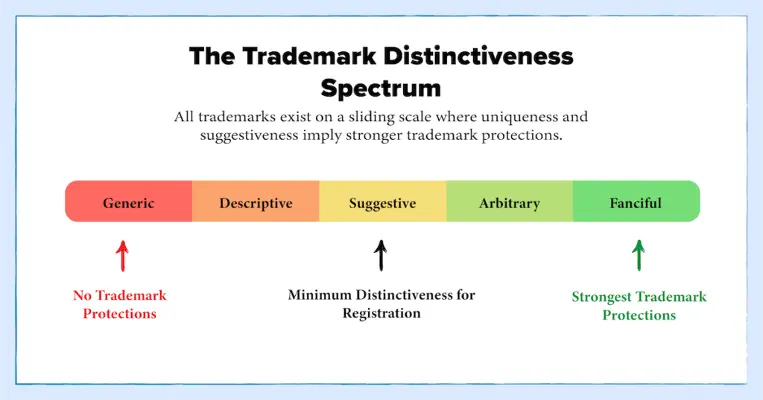

Un Vistazo Rápido al Espectro de Distintividad de Marca

Este gráfico muestra el espectro de distintividad de marca. Cuanto más a la derecha esté tu marca, es más probable que sea distintiva frente a la competencia.

Todas las marcas existen en un espectro de distintividad que se correlaciona directamente con la fortaleza de las protecciones de propiedad intelectual que se otorgan a la marca.

Este espectro de distintividad se puede dividir en varias secciones, cada una proporcionando niveles progresivamente más fuertes de distintividad y protecciones de marca:

- Genéricas — Marcas que utilizan el nombre común para un producto o servicio en particular.

- Descriptivas — Marcas que describen un atributo particular de un producto o servicio.

- Sugestivas — Marcas que sugieren o insinúan un atributo particular de un producto o servicio.

- Arbitrarias — Marcas que no tienen correlación con el producto o servicio al que están asociadas.

- Fantasiosas — Marcas completamente inventadas que no tienen un significado formal en el idioma fuera de su uso como marca.

A continuación, detallaremos cada una de estas categorías de distintividad.

Sin embargo, ten en cuenta que todas las marcas existen en un espectro subjetivo de distintividad, y no existen pautas estrictas sobre dónde trazar la línea entre cada categoría.

Es fundamental elegir una marca que esté lo más lejos posible de lo descriptivo, ya que las marcas descriptivas no reciben protecciones legales bajo la ley de marcas.

Genéricas

El término "marca genérica" generalmente se refiere a aquellas marcas que usan el nombre común de un producto o servicio en lugar de intentar diferenciarse de la competencia.

Por ejemplo, una tienda podría vender una bolsa con las palabras "Tortilla Chips" como opción genérica. Sin embargo, sería imposible obtener protecciones de marca para dicha marca.

Es importante destacar que esta es una de las razones por las cuales las formas "genéricas" de medicamentos (como el acetaminofén en lugar de Tylenol) son relativamente comunes y más baratas que sus competidores con marcas registradas, ya que pueden producirse y venderse a precios mayoristas sin necesidad de un presupuesto de marketing o gastos administrativos adicionales.

Desde un punto de vista legal, nunca es ventajoso comercializar tu negocio bajo un nombre genérico porque (1) no proporciona ninguna protección de propiedad intelectual y (2) no ofrece una ventaja competitiva que ayude a que tu negocio se destaque de tus competidores.

Calificación de Marca: Nunca debes usar un nombre de producto o servicio genérico para comercializar tu marca

Descriptiva

Las marcas descriptivas generalmente incluyen palabras o frases que describen un atributo central de una marca, producto o servicio de manera que genera una comparación o cualificación directa de ese atributo.

En la mayoría de los casos, las marcas descriptivas no pueden obtener protecciones de marca, excepto en aquellos donde la marca invierte una cantidad considerable de tiempo, esfuerzo y recursos para lograr que la palabra o frase adquiera un "significado secundario" en relación con la marca principal.

Por ejemplo, American Airlines (una aerolínea que brinda servicios en las Américas) e International Business Machines (IBM) (una empresa de TI y consultoría) son marcas descriptivas que han obtenido protecciones de marca con el tiempo al adquirir dicho significado secundario.

En términos simples, si una marca descriptiva se usa y promociona exclusivamente como si fuera una marca registrada durante un período prolongado, esa marca puede ganar un significado secundario relacionado con la marca y, por lo tanto, ser registrada como marca principal.

Sin embargo, debes tener en cuenta que esta es una estrategia inherentemente arriesgada debido a la dificultad relativa y el costo de lograr un significado secundario para una marca descriptiva.

En general, esta estrategia solo es ventajosa para grandes empresas (como McDonald’s o Johnson & Johnson) que cuentan con los recursos de marketing para obtener reconocimiento nacional para su marca.

Calificación de Marca: Debes evitar las marcas descriptivas a toda costa. Esto se debe a que las marcas descriptivas (incluidas aquellas con apellidos o palabras como "mejor" o "calidad") carecen de distintividad y generalmente no reciben protecciones bajo la ley de marcas sin obtener primero un significado secundario como se describió anteriormente.

Sugestiva

Una marca sugestiva está compuesta por palabras o frases que solo sugieren o insinúan una cualidad particular o un elemento de la marca, producto o servicio sin llegar a describir el producto en sí.

Por ejemplo, la marca "Netflix" se construye mediante una combinación de las palabras "net", que hace referencia a internet, y "flicks", un sinónimo de películas.

Otras marcas sugestivas notables incluyen "Microsoft" (una combinación de "microcomputadora" y "software"), KitchenAid (refiriéndose a productos que brindan "ayuda" en la cocina), y Greyhound buses (refiriéndose al perro de carreras).

En términos simples, las marcas sugestivas están entre las descriptivas y las arbitrarias al solo insinuar una cualidad o atributo relacionado con la marca principal (como "velocidad," "eficiencia" o un componente material como "microcomputadora").

Calificación de Marca: Las marcas sugestivas ofrecen un buen equilibrio entre protecciones de marca significativas y el atractivo comercial, facilitando su marketing al público.

Dicho de otra manera, las pequeñas empresas pueden obtener suficientes protecciones de marca a través de marcas sugestivas sin tener que invertir tantos recursos de marketing para educar al público sobre la marca, producto o servicio.

Aunque las marcas arbitrarias y fantasiosas suelen ser más ventajosas para empresas con mayores presupuestos, las marcas sugestivas representan un buen punto medio para pequeñas y medianas empresas que pueden depender de listados locales y búsquedas como "plomero cerca de mí" para atraer nuevos clientes.

Arbitraria

Una marca arbitraria está compuesta por palabras o frases que tienen un significado común en un idioma determinado, pero sin relación sugestiva o descriptiva con la marca, producto o servicio en cuestión.

Por ejemplo, en inglés, la palabra "banana" no tiene nada que ver con computadoras u otra forma de tecnología.

Por esta razón, si una empresa decidiera llamarse "Banana" y vender computadoras, esta marca sería de naturaleza "arbitraria" debido a la desconexión entre la palabra y el producto.

Algunos ejemplos de marcas arbitrarias comunes incluyen Apple (computadoras), Dove (chocolates), Camel (cigarrillos) y Shell (gasolineras).

Calificación de Marca: Las marcas arbitrarias se consideran inherentemente distintivas (ya que no sugieren ni describen nada sobre el producto o servicio al que se relacionan) y, por lo tanto, poseen fuertes protecciones de marca.

Sin embargo, dado que muchas marcas arbitrarias incluyen palabras relativamente comunes (como "apple" o "camel"), es crucial realizar una búsqueda exhaustiva de marcas registradas para asegurarse de que nadie más haya utilizado o esté utilizando actualmente la palabra o frase en una industria similar.

Fantasiosa o Inventada

Una marca fantasiosa o inventada solo adquiere significado cuando se aplica a los productos y la marca de un negocio en particular.

En otras palabras, son palabras o frases "inventadas" únicamente como herramienta de marketing y no tienen definición o significado fuera del contexto de la marca, producto o servicio.

Algunos ejemplos famosos de marcas fantasiosas incluyen "Xerox" para fotocopiadoras o "Nikon" para equipos eléctricos de precisión.

Para ampliar esto, las marcas fantasiosas suelen ser errores ortográficos, abreviaturas o juegos de palabras utilizados para comercializar la marca de manera divertida o interesante.

El nombre Nikon, por ejemplo, es una abreviatura occidentalizada del nombre original completo de la compañía que usó para comercializar equipos de cámara en las décadas de 1930 y 1940.

Específicamente, "Japan Optical Industries Corporation" (日本光学工業株式会社) se convirtió en "Nikkō" (日光), que luego fue occidentalizado a "Nikon."

Calificación de Marca: Las marcas fantasiosas o inventadas están en el extremo más alto del espectro de distintividad y reciben la mayor protección bajo la ley de marcas.

Sin embargo, también puede tomar una cantidad significativa de tiempo, dinero y esfuerzo comercializar una marca fantasiosa o inventada al público, ya que presentan una barrera mayor para el reconocimiento de marca.

Por qué la distintividad de marca es importante?

La distintividad de marca es el elemento más importante para determinar la solidez de tus derechos de propiedad intelectual.

En términos simples, la distintividad de marca es crucial porque es el primer paso en el proceso legal para obtener protecciones de propiedad intelectual para tu marca, producto o servicio.

Específicamente, el proceso para obtener protecciones de marca para tu negocio generalmente sigue un camino lógico:

- Determina si la marca es lo suficientemente distintiva como para causar confusión en los consumidores si otra marca comenzara a utilizarla. Si es así:

- Realiza un análisis de costo-beneficio para determinar si tu negocio se beneficiaría al registrar la marca como una marca registrada. Si es así:

- Intenta registrar la marca en el Registro Principal para obtener protecciones de marca para tu negocio. Si tienes éxito:

- Presenta una combinación de la Declaración de Uso de la Sección 8 y la Declaración de Incontestabilidad de la Sección 15 después de cinco años de uso continuo para demostrar que la marca sigue utilizándose en el comercio y para obtener protecciones de incontestabilidad para tu marca (una forma significativamente más sólida de protección de PI). Después de eso:

- Presenta otra Declaración de Uso de la Sección 8 así como un formulario de Renovación de Registro de la Sección 9 después de diez años de uso continuo para renovar tu marca. Luego, renueva tu uso cada diez años a partir de entonces.

Observa cómo todo el proceso se basa en la idea de reducir la confusión del consumidor al ofrecer protecciones a las marcas que son distintivas frente a sus competidores.

Esta idea de proteger al consumidor es central para todo el marco legal que rodea a las marcas registradas, ya que asegurar que los consumidores puedan confiar en que los productos y servicios que están comprando son auténticos es el objetivo principal de la ley de marcas.

De la misma manera, garantizar que tu marca se distinga de la competencia es una excelente forma de fomentar la confianza del consumidor en tu marca y una excelente manera de construir una audiencia leal a lo largo del tiempo.

Sin embargo, todo esto comienza con asegurar que tu marca registrada sea lo suficientemente distintiva como para caer dentro de las categorías sugestiva, arbitraria o fantasiosa, ya que estas son las únicas que reciben protección según la legislación actual de marcas en los Estados Unidos.

Factores Polaroid y Cómo Determinar la Fortaleza de tu Marca Registrada

Los tribunales considerarán varias variables (como los factores Polaroid y DuPont que se describen a continuación) en los casos de infracción de marcas. Trabajar en función de estos factores puede ayudarte a elegir una marca sólida.

Como hemos mencionado varias veces a lo largo de este artículo, la distintividad de marca es el aspecto más importante a tener en cuenta al determinar la fortaleza de tu marca.

Sin embargo, a veces puede ser difícil determinar cuán distintiva es una marca en el contexto general.

Aquí es donde entra en juego la jurisprudencia.

Específicamente, en 1961, la Corte de Apelaciones del Segundo Circuito de EE. UU. falló en el caso Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961).

En este caso, Polaroid Corporation (propietaria de la marca "Polaroid" y de otras 22 marcas similares) presentó una demanda contra Polarad Electronics Corporation, alegando que la marca Polarad era demasiado similar a la suya (es decir, "no distintiva") y provocaba confusión entre los consumidores.

El núcleo del caso fue la cuestión de si los productos electrónicos de Polarad (hornos de microondas y televisores) estaban demasiado cerca en identidad de los productos de cámaras de Polaroid.

Sin embargo, el caso también planteó un punto más amplio: "¿cómo calificamos la distintividad?" en situaciones donde dos marcas operan en espacios similares, aunque distintos.

La respuesta, al menos en este caso, es considerar la suma de varios factores para determinar la fortaleza de la marca anterior.

Específicamente:

Cuando los productos son diferentes, las posibilidades de éxito del propietario anterior son una función de muchas variables: la fortaleza de su marca, el grado de similitud entre ambas marcas, la proximidad de los productos, la probabilidad de que el propietario anterior cierre la brecha, la confusión real, la buena fe del acusado al adoptar su propia marca, la calidad del producto del acusado y la sofisticación de los compradores. Incluso este catálogo exhaustivo no agota todas las posibilidades; el tribunal puede tener que considerar otras variables.

Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492, 495 (2d Cir. 1961).

Esta cita establece factores específicos (más la nota de "otras variables") a los que ahora los tribunales se refieren como "factores Polaroid de distintividad de marca".

actores Dupont: Otra Forma de Probar la Fortaleza de tu Marca

Estos factores fueron reafirmados una década después en el caso pplication of E.I. DuPont DeNemours & Co., 476 F.2d 1357, 1361 (C.C.P.A.1973) , donde los factores se ampliaron a una lista de 13 factores específicos que los tribunales deben considerar al determinar la probabilidad de confusión.

Específicamente, al evaluar la probabilidad de confusión, el tribunal debe considerar cada uno de los siguientes factores:

- La similitud o disimilitud de las marcas en su totalidad en cuanto a apariencia, sonido, connotación e impresión comercial.

- La similitud o disimilitud de los bienes o servicios tal como se describen en una solicitud o registro o en relación con lo que una marca anterior abarca en su registro.

- La similitud o disimilitud en los métodos de distribución, como canales comerciales específicos.

- Las condiciones bajo las cuales los compradores a quienes se dirige la marca compran, por ejemplo, "impulsivas" frente a "cuidadosas y planificadas".

- La fama de la marca anterior (ventas, publicidad, duración de uso).

- La cantidad y naturaleza de marcas similares en el mercado para bienes similares.

- La naturaleza y alcance de la confusión real.

- La duración del tiempo y condiciones bajo las cuales ha existido el uso simultáneo sin evidencia de confusión real.

- La variedad de bienes en los que una marca se utiliza o se puede utilizar (marca de casa, marca de familia, marca de producto).

- La relación en el mercado entre el solicitante y el propietario de una marca anterior: (a) si hay un "consentimiento" para registrar o usar; (b) disposiciones de acuerdo diseñadas para evitar confusión, por ejemplo, limitaciones de uso; (c) cesión de la marca, aplicación, registro y buena voluntad con la marca; (d) renuncia y prohibición atribuibles al propietario de la marca anterior que indican falta de confusión.

- La medida en que el solicitante tiene derecho a excluir a otros del uso de su marca en sus bienes.

- La magnitud de la posible confusión, es decir, si el error es mínimo o sustancial.

- Cualquier otro hecho establecido como prueba del efecto de uso.

Integrándolo Todo: Cómo Determinar la Fortaleza de tu Marca a través de su Distintividad

Al determinar la fortaleza y distintividad relativa de tu marca, es inteligente abordar el mercado desde la perspectiva de estas dos listas de factores.

Por ejemplo, tomando los factores finales de la lista Polaroid, ¿cuál es la calidad relativa de tu producto en comparación con otros productos en tu industria? ¿A qué tipo de audiencia te diriges con tus productos, y qué tan probable es que se confundan al comprar tu producto frente a uno de otro?

Si tu producto es de una calidad relativamente igual al resto del mercado y tu audiencia objetivo es más probable que se confunda con un producto similar (como si vendes directamente a consumidores en lugar de compradores sofisticados en un mercado B2B), puede que necesites establecer una marca más distintiva (es decir, arbitraria o imaginaria), ya que una marca meramente sugerente puede no ser suficiente para diferenciar tu identidad de marca.

En otras palabras, la fortaleza de una marca puede cambiar dependiendo del contexto en el que se use y de la distintividad relativa de la marca.

Cuanto más amplio sea tu mercado, más distintiva tendrá que ser tu marca para destacar entre la competencia.

O, dicho de otra manera:

- Las marcas genéricas son inherentemente débiles porque no existen contextos en los que sean lo suficientemente distintivas como para proporcionar protecciones legales

- Las marcas descriptivas también son inherentemente débiles, ya que las marcas que son meramente descriptivas no reciben protección bajo registro de marca a menos que adquieran un significado secundario. Esto generalmente requiere una gran inversión de tiempo y dinero.

- Las marcas sugerentes tienen una fortaleza relativamente neutral porque pueden ser distintivas en la mayoría de los contextos, aunque podrían enfrentar presión de marcas competidoras a nivel nacional.

- Las marcas arbitrarias son generalmente fuertes siempre y cuando ninguna otra marca haya usado el término en el comercio para comercializar un producto o servicio similar. La ausencia de una relación directa entre la marca y el producto o servicio en cuestión hace que la marca sea inherentemente distintiva en todos los contextos, sin un uso previo.

- Las marcas imaginarias o creadas ofrecen la mayor protección de marca porque suelen ser palabras inventadas sin uso o definición fuera de la comercialización de la marca. Esto las hace inherentemente distintivas y dignas de la máxima protección.

En resumen: la fortaleza de una marca está intrínsecamente ligada a su distintividad, que a su vez se determina a través de factores contextuales como la sofisticación de la audiencia, la calidad o los atributos del producto, y los canales y mercados en los que se planea utilizar la marca.

Las marcas arbitrarias e imaginarias son preferidas porque poseen una distintividad inherente, siempre y cuando nadie haya utilizado previamente la marca en cuestión.

Por otro lado, las marcas sugerentes generalmente necesitan demostrar que no son "meramente descriptivas", lo cual, de no lograrse, resultaría en la pérdida de sus protecciones de marca.

Conclusión: Lograr el equilibrio adecuado entre la distintividad legal y la comerciabilidad de tu marca es clave para determinar la fortaleza relativa de tu marca, producto o servicio.

Preguntas Frecuentes sobre la Distintividad de Marcas

La mayoría de las preguntas que puedas tener sobre el registro de marcas y la distintividad se pueden responder mediante una búsqueda rápida en el sitio web de la USPTO o hablando con un abogado experimentado.

Aquellas personas que desean registrar una marca para su negocio a menudo tienen preguntas sobre el proceso.

Por esta razón, la USPTO publica una lista de más de 300 preguntas frecuentes que ayuda a los individuos que registran por primera vez.

Aquí responderemos algunas de las preguntas más comunes que recibimos, pero ten en cuenta que la USPTO publica recursos adicionales en su sitio web en caso de que necesites información más específica sobre el proceso de registro de marcas.

¿Qué es la distintividad de marca?

El término "distintividad de marca" se refiere a la capacidad de un consumidor de identificar y distinguir una marca, producto o servicio de sus competidores.

Las marcas genéricas y descriptivas generalmente se consideran sin distintividad y, por lo tanto, no reciben protección bajo la ley de marcas registrada.

Las marcas sugerentes, arbitrarias e imaginarias se consideran inherentemente distintivas, lo cual les otorga protección bajo la ley de marcas registrada.

Es importante destacar que la distintividad es un elemento clave tanto en el proceso de registro de marcas como en los litigios por infracción de marca. La ley de marcas registrada está basada en reducir la confusión del consumidor al garantizar que los productos y servicios de diferentes marcas sean suficientemente distintos.

¿Por qué mi marca necesita ser distintiva? La USPTO solo te permitirá registrar marcas que sean distintivas, lo que significa que las marcas genéricas o descriptivas no pueden obtener protecciones.

¿Por qué mi marca necesita ser distintiva?

La USPTO solo te permitirá registrar marcas que sean distintivas, lo que significa que las marcas genéricas o descriptivas no pueden obtener protecciones.

Por esta razón, otras empresas pueden usar tu marca sin repercusiones si esta no posee suficiente distintividad.

¿Qué son las clases de marcas y cómo se relacionan con la distintividad?

Generalmente, tu marca solo necesita ser distintiva dentro del sector específico en el que trabajas.

Por eso, por ejemplo, Delta Faucets y Delta Airlines pueden coexistir al mismo tiempo, ya que una ofrece productos de baño y la otra servicios aéreos.

La USPTO reconoce 45 clases de marcas individuales que corresponden a todos los productos y servicios que se pueden vender en el país.

Cuando registras una nueva marca, tendrás que elegir una o más de estas clases para registrarla.

Es importante destacar que las protecciones de tu marca solo se aplicarán a los productos y servicios que entren en la clasificación que elijas, lo que significa que tu marca solo necesita ser distintiva dentro de las clases que selecciones.

¿Cómo puedo saber si mi marca es sugerente o meramente descriptiva?

No puedes. Sin importar lo que alguien diga, la determinación final de si una marca es sugerente o descriptiva recae en el criterio del abogado de la USPTO que revise tu solicitud.

Debido a que el proceso es subjetivo, es esencial que siempre optes por una marca que se incline hacia el lado "arbitrario" en lugar del descriptivo.

¿Cuál es la diferencia entre el registro principal y el registro suplementario para marcas?

Las marcas que se determinan como inherentemente distintivas se registran en el registro principal de la USPTO y, por tanto, obtienen todas las protecciones legales bajo la ley de marcas de EE. UU.

Las marcas que se consideran descriptivas pero que tienen el potencial de obtener un significado secundario pueden aparecer en el registro suplementario.

La diferencia clave es que las marcas en el registro suplementario solo obtienen las siguientes protecciones:

- El propietario de la marca puede presentar demandas federales de infracción para combatir marcas competidoras.

- La USPTO no permitirá que otros negocios registren marcas confusamente similares.

- La marca aparecerá en los informes de búsqueda de marcas como si estuviera en el registro principal.

- El propietario de la marca puede usar el símbolo de marca registrada (®) para indicar su estatus.

En cambio, las marcas en el registro suplementario no tienen acceso a las siguientes protecciones:

- No pueden solicitar incontestabilidad después de cinco años de uso.

- No tienen la presunción legal de validez, propiedad o distintividad (deberán probar estos aspectos en litigios).

- No tienen la presunción de derecho exclusivo para usar la marca en el comercio.

- La Oficina de Aduanas y Protección Fronteriza de los EE. UU. (CBP) no detendrá la importación de productos que infrinjan la marca.

- Las agencias federales no perseguirán penalmente a individuos o empresas que falsifiquen los productos.

- No puedes usar el registro en el registro suplementario como base para una solicitud de marca extranjera.

Puntos Clave

Para resumir, asegúrate de que tu marca sea sugerente, arbitraria o imaginativa, y que ninguna otra empresa o marca la haya utilizado en tu industria, antes de registrarla en la USPTO.

La distintividad de la marca existe en un espectro que va desde lo genérico (sin distintividad) hasta lo imaginativo o inventado (sin significado fuera de su uso como marca registrada).

Todas las marcas potenciales se encuentran en algún lugar de este espectro, según lo determine el criterio del abogado de la USPTO que revise tu solicitud.

Por esta razón, es fundamental que elijas una marca que se ubique lo más lejos posible del lado genérico/descriptivo del espectro.

Si tienes alguna duda sobre la distintividad de tu marca, es esencial que consultes a un abogado inmediatamente para determinar si vale la pena registrar la marca.

Como hemos mostrado en este artículo, la distintividad relativa de tu marca impactará directamente la solidez de las protecciones de marca que recibas y tus posibilidades de éxito en una posible demanda de infracción en el futuro.

Por esta razón, la distintividad es clave para construir una marca fuerte que impulse a tu negocio hacia un futuro exitoso y rentable.

Recursos Clave

- Manual de Procedimientos de Examen de Marcas § 1209.01 - Continuo de Distintividad / Descriptividad.

Lecturas Adicionales

- Diferencias Clave entre el Registro Suplementario y el Registro Principal para Marcas

- Ley de Marcas de los Estados Unidos: La Guía Definitiva

- ¿Qué es la "Probabilidad de Confusión" en la Ley de Marcas?

Otros Recursos

- Preguntas Frecuentes sobre Marcas | USPTO — Una publicación de la USPTO que responde a más de 300 preguntas comunes sobre el proceso de registro de marcas.

- Problemas Comunes en Solicitudes | USPTO — Una publicación de la USPTO que cubre algunos problemas comunes que enfrentan los nuevos solicitantes al intentar registrar una marca.